The impressionist movement is characterized by fluid aesthetic dialogues resulting from a constant flux of people and paintings. An interest in painting outdoors, connecting the viewer with specific observations of place and capturing momentary effects, appears in many parts of the world in the late nineteenth century. Although impressionism is often perceived as a French creation, the core group of exhibiting artists in the 1870s was international, and the movement found strength in embracing diversity of technique from outside France. Without stylistic inventions and cultural traditions from all over the globe, impressionism might have begun and ended with the Paris exhibitions of the 1870s and 1880s. Artists featured in this section began experimenting with impressionism while in France, but as they crossed borders, they applied the style to new settings infused with local traditions. From the global travels of Lilla Cabot Perry, Anna Richards Brewster, and Dawson Dawson-Watson, to the seascapes of Thomas Meteyard and Childe Hassam, to the explorations of the seasons in works by Søren Emil Carlsen, Hamilton Hamilton, Robert Emmett Owen, and Chauncey Ryder, adaptation to local settings is evident.

Zoe Lakin and Michael Harding

Lilla Cabot Perry invokes a sense of serenity in this landscape, which places the viewer on a path entering a forest bathed in soft light streaming down from the treetops. This painting may have been made during one of her visits to Japan from 1899 to 1901 or perhaps in the tranquil countryside during her many summer days in the artists’ colony in Giverny, France. The artist’s love of poetry shines through in this painting in the almost audible sense of peace, harmony, and beauty represented through her subtle handling of momentary light and color.

Zoe Lakin, Class of ’22

Lilla Cabot Perry, (American, 1848–1933), The Forest, n.d., oil on canvas, Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art, Auburn University; gift of Fred D. Bentley, Sr.

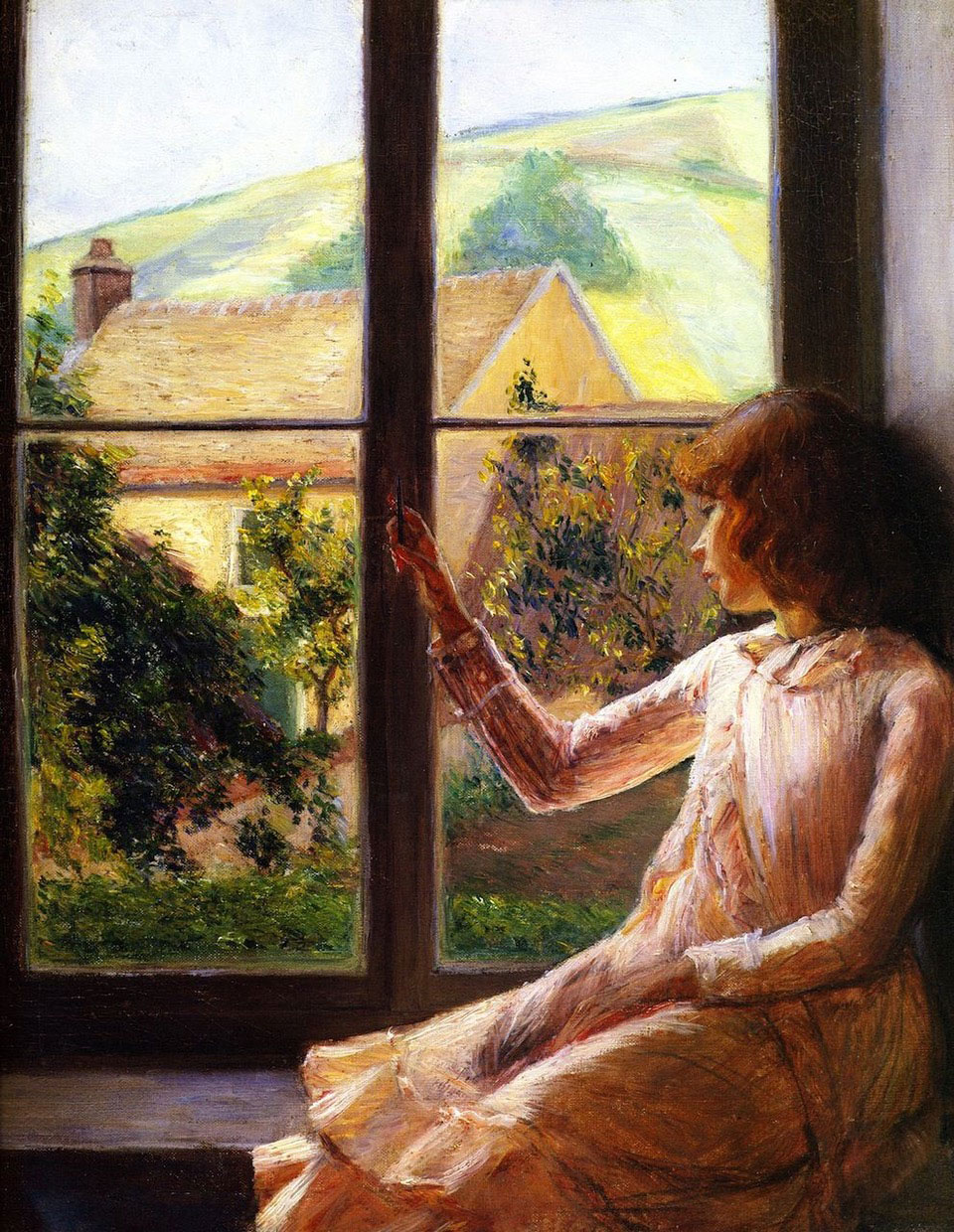

Lilla Cabot Perry’s painting features many characteristics of impressionism, which the artist adopted during her long stays in France. She spent a substantial amount of time with Claude Monet, who told her to “… try to forget what objects you see before you, a tree, a house, a field or whatever… and paint it just as it looks to you, the exact color and shape, until it gives you your own impression of the scene before you.” Based on similar works such as Child in Window reproduced here, The Tea Party likely depicts Perry’s daughter Edith and the family cat Lierre during a brief summer visit back to Boston, Massachusetts. The light delicately filtering down onto the girl, cat, and tablecloth illuminates, but also colors the scene. Painted with impasto in hues of blue, green, and bright purple on the tablecloth, it bursts into the upper right corner of the painting in an explosion of thickly painted, vibrant colors ranging the full spectrum.

Zoe Lakin, Class of ’22

Lilla Cabot Perry, (American, 1848–1933), (right) The Tea Party, 1890, oil on canvas, private collection. Lilla Cabot Perry, (left) Child in Window, 1891, oil on canvas, private collection.

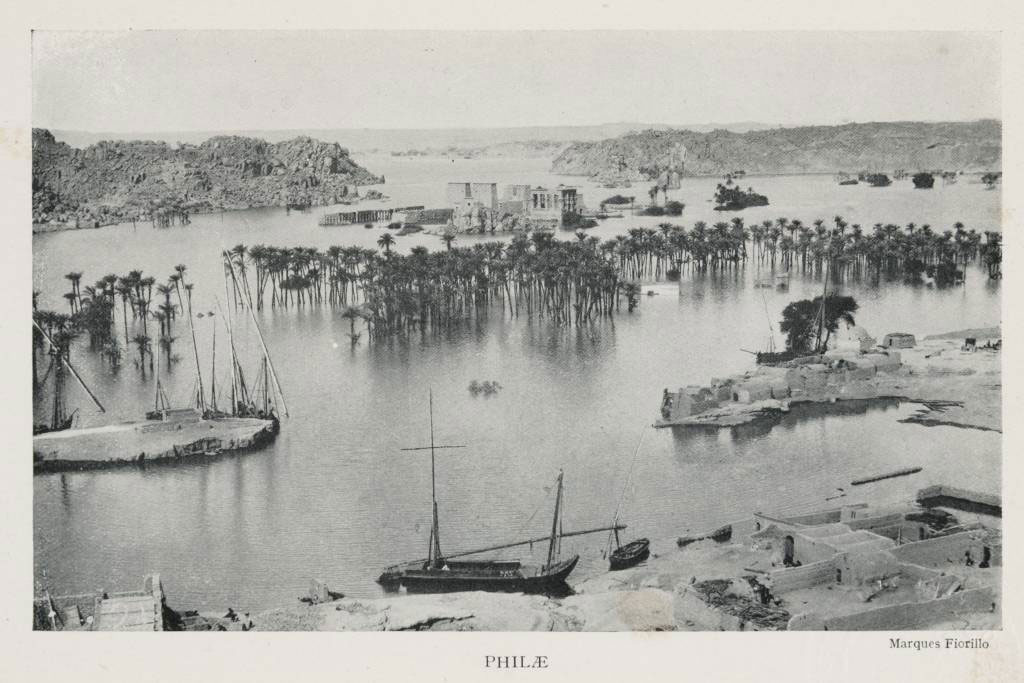

Anna Richards Brewster captures the light peeking into a darkened corner of the ancient Egyptian columns at the Philae Temple. Flood waters reflect the sunlight, masterfully expressed with quick strokes implying the spontaneity of a moment. The artist depicts the remaining paint of the hieroglyphics inscribed in the background as though colorful gemstones. Brewster’s overall palette suggests a serious and solemn mood, as if she is reflecting on the somber future of a lively past. The site at Philae was threatened by the flood waters caused by the British dam built on the Nile in 1902. Perhaps this attention to forces of destruction reminded her of her son’s recent, untimely death. As the postcard reproduced here shows, Brewster would have reached the site by boat. It is unknown if she finished Columns at Philae, Egypt on board. Why might she have found it important to portray this scene from the boat?

Christina Hancock, Class of ’22

Left: Anna Richards Brewster, (American, 1870– 1952), Columns at Philae, Egypt, 1912, oil on canvas, lent by the Montgomery Museum of Art, Montgomery, Alabama; gift of the Estate of James L. Whitehead and Elliott P. Ellis.

Right: Marques & Fiorillo, Philae, In A.B. De Guerville, “New Egypt.” E. P. Dutton & Company, New York, 1906.

The son of a prolific English illustrator, Dawson Dawson-Watson adopted impressionism during his studies in France beginning in 1886. Following other artists, including Claude Monet, Thomas Buford Meteyard, and Lilla Cabot Perry to Giverny, France, Dawson-Watson painted popular subjects like the grain stacks that occupied the fields near the village. His diagonal strokes of pastel colors and deep purples reveal his buildup of paint on the surface. Passed through descendants of the family who owned a local hotel, this painting is believed to have been Dawson-Watson’s payment for lodging in Giverny.

Elizabeth Beasley, Class of ’20

Dawson Dawson-Watson, (English-American, 1864–1939), Les Meules (Grainstacks), ca. 1888–93, oil on canvas, Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art, Auburn University; museum purchase with funds provided by Judge and Mrs. Bo Torbert and Mr. and Mrs. Ed Lee Spencer.

Frederick Childe Hassam was an impressionist painter in the United States and a member of “The Ten,” a collective of artists who used the style to depict local landscapes and also scenes in Paris, a city he frequented. There he painted from the studio of the famed French photographer, caricaturist and balloonist, Nadar, who lent his studio for the first impressionist exhibition, located in the same building where Frank Myers Boggs also painted. In Broad Cove, Hassam portrays a swimming hole at low tide beneath a looming slab of rock at Appledore, one of the nine Isles of Shoals off the coast of New Hampshire. The expressive features of the cove are depicted through intense color, but the composition as a whole remains flat and nearly abstract with daring and dramatic brushwork in watercolor, especially compared with the slow recession in Meteyard’s delicate watercolor nearby. Hassam imitates the instantaneity of impressionist brushstrokes but translates it into his own unique fragmentary style.

Leslie Schuneman, Class of ’20

Frederick Childe Hassam, (American, 1859–1935), Broad Cove, Appledore, 1912, watercolor on wove paper, lent by the Columbus Museum, Columbus, Georgia; gift of Hirschl & Adler Galleries, Inc.

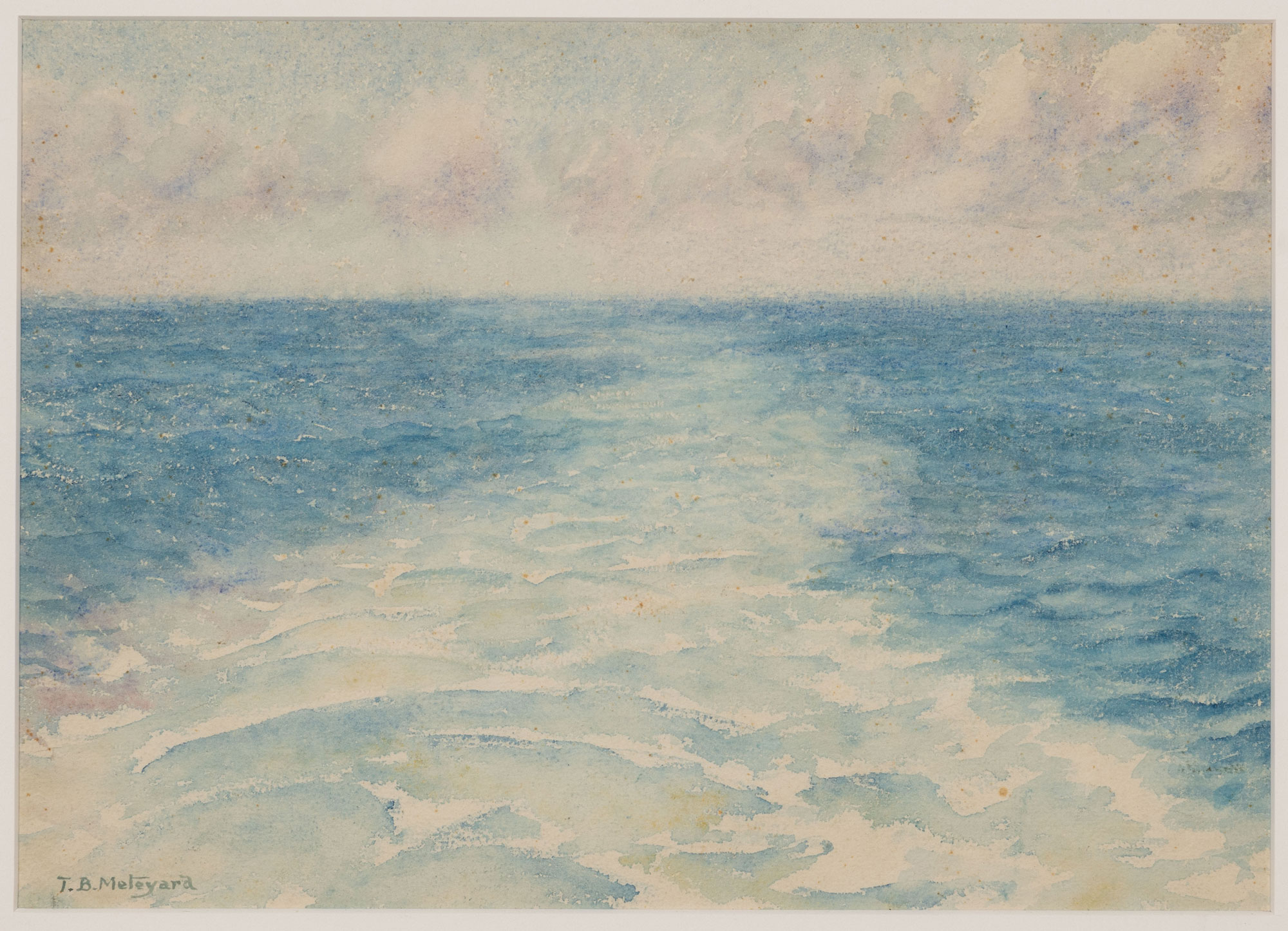

Described by a critic as “unusually delicate,” Thomas Buford Meteyard’s palette includes unexpected combinations of hues such as the purples and yellows within the vast waters seen in Mid-Atlantic. Another reviewer observed that the artist looked with “unclouded eyes,” allowing his viewers to feel the breeze off the Atlantic Ocean through expressive brushstrokes and striking colors. While regarded as an impressionist, Meteyard did not fully identify with the term, fearing the implications of the label. Striving to reflect his individual style, Meteyard wrote, “… it is better to fail altogether than to be like the crowd that see and paint through another man’s eyes.”

Avery Grace Agostinelli, Class of ’21

Thomas Buford Meteyard, (American, 1865–1928), Mid-Atlantic, ca. 1890, watercolor on paper, Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art, Auburn University; gift of the Meteyard Family.

Robert Emmett Owen was already an accomplished illustrator by the time he began producing his impressionist landscapes of the Connecticut countryside. After buying a rural house, he experimented with vibrant colors and thick, open brushwork. With its veil of snow partially obscuring the road and nearby houses, Owen pairs the chaos of a storm with the pinkish color of twilight in Snowstorm.

Elizabeth Beasley, Class of ‘20

Robert Emmett Owen, (American, 1878–1957), Snowstorm, ca. 1912, oil on canvas, lent by the Dixon Gallery and Gardens, Memphis, Tennessee; gift of Susan and John Horseman in honor of Kevin Sharp.

After studying painting abroad and befriending American painter William Merritt Chase, Hamilton Hamilton began to experiment with impressionism, turning mostly to plein-air painting in 1875. Translated into his own style, the artist places the viewer on a path to walk into and explore an apple orchard in full bloom. He uses a muted, earth-toned palette which underscores blossoms that project off the canvas, inviting his audience to experience the spring alongside him through his technique and colors.

Leslie Schuneman, Class of ’20

Hamilton Hamilton, (English-American, 1847–1928), Apple Orchard, after 1889, oil on canvas, lent by the Columbus Museum, Columbus, Georgia; museum purchase in honor of Frances Cole.

Søren Emil Carlsen’s brushstrokes suggest a fleeting view of the natural world in this wooded scene, which is uninhabited by humankind. While he was best known for painting more closely rendered still-lifes, the artist also depicted outdoor scenery, especially forests. Carlsen took what he learned from the impressionist painters of France while there from 1884 to 1886 and translated the new techniques into his work. Compared with the more expansive views nearby, he more tightly framed his subject. This type of composition is akin to his still-life paintings, such as the example illustrated below. The pronounced brushstrokes suggest wind blowing the leaves and the thickly applied paint, or impasto, draws attention to the idea that the painting translates a specific moment in time.

Søren Emil Carlsen, (Danish-American, 1853–1932), (left), Wooded Interior, 1904, oil on canvas, lent by the Columbus Museum, Columbus, Georgia; museum purchase. Søren Emil Carlsen, (right) China and Cherries, ca. 1895–1900, oil on canvas, private collection.

Chauncey F. Ryder played a key role in the transition of impressionism into modern abstraction. He adopted many key aspects of the movement, such as the use of a palette knife to create thick, unvarying layers of impasto, as well as the practice of painting subjects directly, rather than from memory. In Green Lane, the artist creates a space that although not specifically recognizable, appears real and immediate. Ryder juxtaposes peculiarly bright greens in the foreground with creamy hues of white and blue in the sky, lending a sense of balance to the landscape.

Zoe Lakin, Class of ‘22

Chauncey F. Ryder, (American, 1868–1949), Green Lane, 1930–35, oil on canvas, lent by the Columbus Museum, Columbus, Georgia; bequest of Edward Swift Shorter.