Students in courses, Sculpture as Space and Themes in Contemporary Sculpture at Auburn University, led by Associate Professor Kristen Tordella-Williams, researched and proposed contemporary monuments in response to the exhibition Monuments and Myths: The America of Sculptors Augustus Saint-Gaudens and Daniel Chester French. The students researched, proposed, and built maquettes of future monuments that fill in historical gaps and celebrate marginalized communities and spaces.

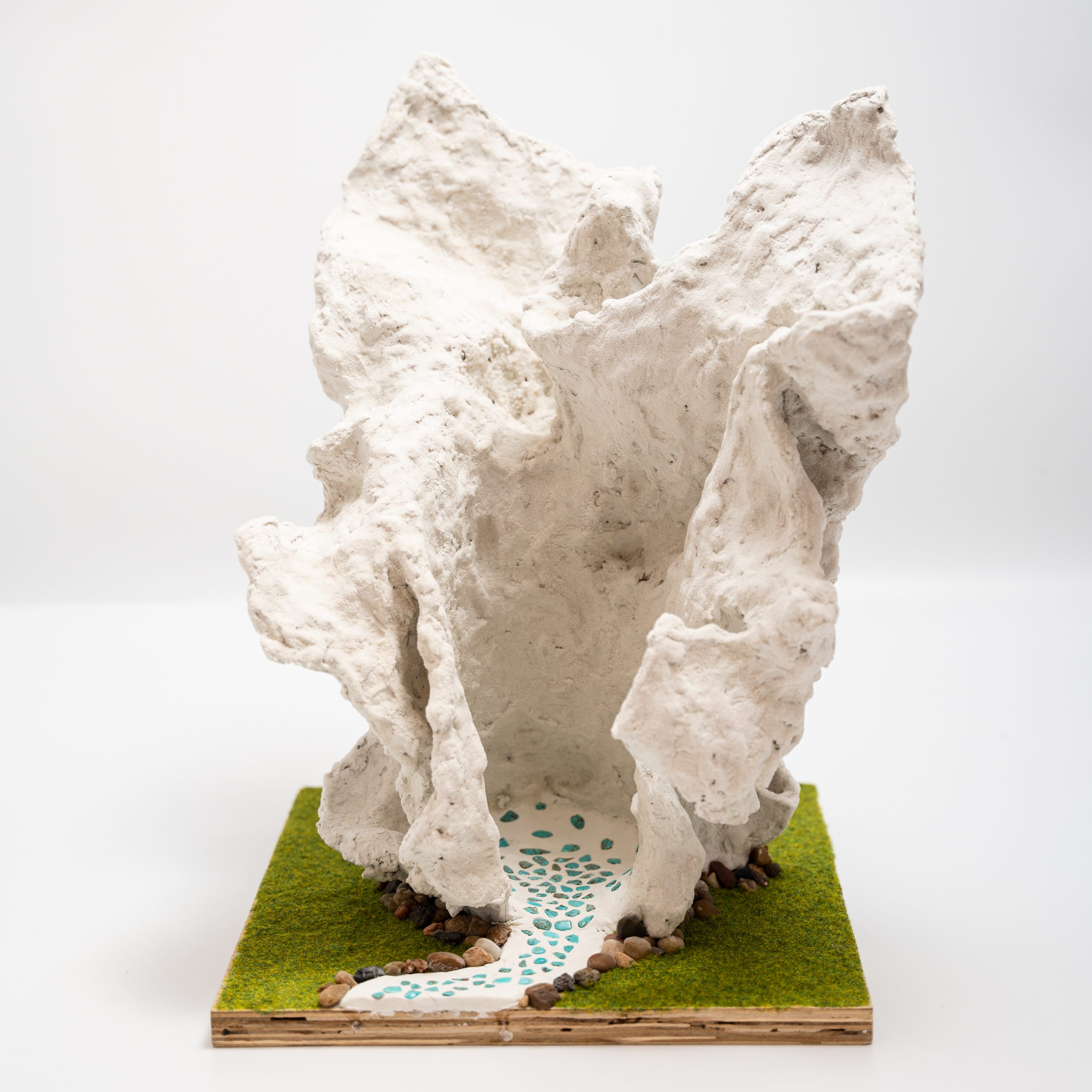

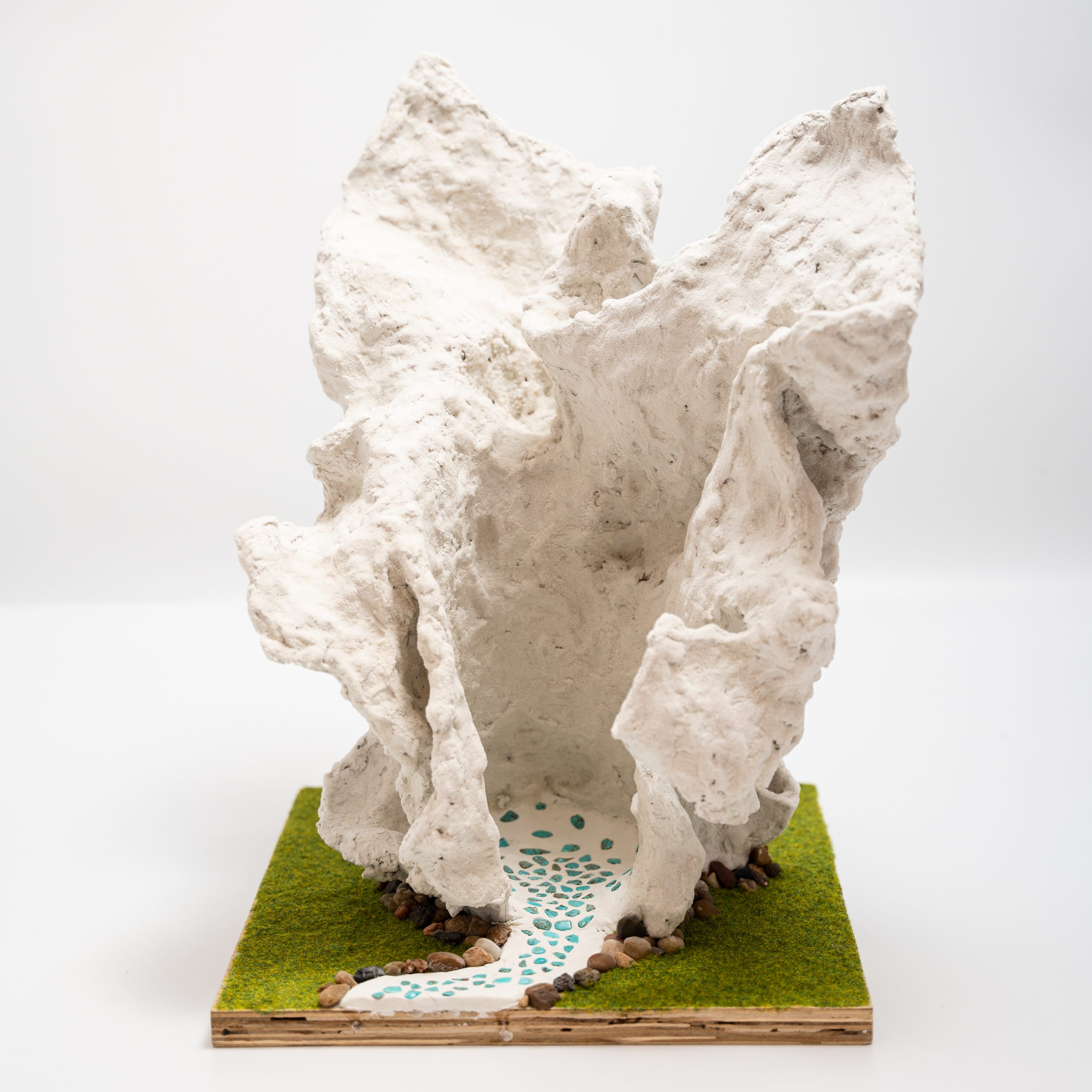

“Into Space” is a monument to celebrate the unrecognized manpower that contributed to spaceflight. It is an effort to unite communities across state lines, ethnicities, and classes –particularly uniting the peoples of southern New Mexico to those of Huntsville, Alabama.

Its form takes inspiration from the exhaust plume left behind after the Saturn V rocket left the ground, which launched the Apollo 11 space shuttle in its voyage to the moon. Into Space also takes inspiration from the landscape of southern New Mexico, referencing the rocky canyons, the white gypsum sand of White Sands National park, and the organic shape of sand blown upward in an explosive fashion.

The intention of the monument is to bring the landscape of New Mexico to Huntsville, in which viewers can be enveloped. It should serve as a form of manufactured environmental art. The sculpture measures 38 feet tall and 28 feet wide at its widest point, with an internal room of 6 feet in diameter at its base; it will serve to enclose the viewer in the desert. From within this twisting mass of sand and rock, the viewer has nowhere to look except up toward the sky – towards space.

Much of the work that laid the foundation for NASA in 1958 occurred in southern New Mexico,

relying on the labor of the people there. Southern New Mexico has a very large Spanish-speaking population, and the culture of the area is heavily inspired by the people’s Hispanic heritage. When NASA moved out of New Mexico to bases in Florida and Huntsville, the people of New Mexico were either forced to migrate across the country with their jobs, or be out of work entirely.

This story is particularly important to me because it is how my grandfather ended up in Huntsville, and with his moving, he became isolated from his family and culture. He, along with so many others, faced discrimination in the workplace to the point where he abandoned the Spanish language almost entirely. He refused to teach his children, and then later his grandchildren, any Spanish because he felt that it would only hold you back in the workplace; English was the language that the world operated in, and to be successful, you had to accept that fact. In the early 1970’s, NASA decided they were going to move in a new direction with their German leadership, and coincidentally let all of the Hispanic people from New Mexico go, prompting discrimination lawsuits and a retraction of this decision on NASA’s part.

NASA was not built exclusively on the backs of the people of southern New Mexico, but they were an important part of its history that are overlooked by the people of Huntsville. “Into Space” serves as a reminder of the work that these people did on the ground in the name of spaceflight.

By Jerryn Puckett

The stained-glass window currently on display at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa showcases the religious and cultural iconography of the Post-Civil War South. Religion has been intertwined with the Southern cause since before the Civil War. In the eyes of the South, slavery and the Southern establishment were a divine right that had been bestowed on them. This divine right needed to be protected; thus, any act of aggression against the South was an act against their religious beliefs. Prior to the Civil War, sermons spread through the South carrying a message of a divine crusade. They preached that it was the responsibility, and destiny, of Southerners to protect morality and Southern virtues from corruption.

Image: Courtesy of Teresa Golson

When the war broke out, it was interpreted as being the peak in a moral crisis and a battle against corruption and virtue. Religion was used to defend the existence of the Southern establishment and was the foundation of Southern culture. Thus, it would be the motivator for them to continue a war.

After the war, there was a desire to create a culture that was even more distinct than other parts of the nation. The solution was to further weave cultural and religious identities into perceptions of Southern defeat. Falling back on the old sermons and the concept of the divine crusade, religion not only explained what had happened, but it also gave many Southerners a community to cling to. The combination of spiritual religion and cultural religion created the narrative of the Lost Cause; an idea that the South had a distinct and superior culture that was pure. The war was not fully lost and if they adhered to their values, they could triumph against impure invaders.

The Monument to Confederate Soldiers and Sailors is a public display located on the State Capitol grounds in Montgomery, Alabama, erected in 1898. With almost 750,000 casualties, the Civil War was the deadliest conflict in American history. Too focused on matters for the living to properly take care of the dead, armies left behind shallow graves, unnamed markers, and hasty memorials in their wake. After Appomattox, a similar question confronted both armies: what to do with their dead soldiers?

Many thought it was the government’s responsibility to handle fallen soldiers. Private organizations and military units set out to find and return the dead due to their rights as citizens of the United States. The same treatment was not afforded the Confederates. Left behind to rot, southern armies spared no resources for this grisly task. As hostilities ceased, Confederate soldiers were not treated the same as Union ones. After all, they were traitors and their rights as citizens were not the same. What, then, should be done with southern dead soldiers and how should they be remembered?

White southerners were desperate to recover the established racial hierarchy lost during the war. No official mechanism to honor Southern soldiers created additional bitterness and humiliation. After the war and well into the 20th century, southern organizations fused these ideas together. Large monuments, placed in conspicuous public spaces, sprouted across the south with the primary function of rewriting the war’s legacy by highlighting the individual soldier’s sacrifice rather than the racist-infused Confederate government.

The dedication speeches emphasized the soldier’s devotion to duty, sacrifice, and bravery. More prominent were explicit references to Alabama’s rights to slavery, stating that the “Anglo-Saxon race” was superior to all other races, reflective of the times when white supremacy was an accepted ideology. This 88-foot tall monument, on an extraordinarily prominent position on public grounds, memorializes and misremembers false ideas that Confederate soldiers fought valiantly in support of a righteous cause. Its purpose is not controversial. It was designed and remains a symbol of hate, bigotry, and a morally corrupt society desperate to remember the power they once had.

By Patrick Ward

How do you celebrate a man without knowing his cause? Joe Cain, credited with the revival of Mobile, Alabama’s Mardi Gras tradition, represents both a city’s celebration and a Confederate narrative. Depicted as Chief Slacabamorinico in Mardi Gras Park in Mobile, AL, Cain represents the every-man once a year during the “People’s Parade” leading to Mardi Gras. This tradition stems from his revival of Mardi Gras during the mid-1860s, in defiance of the Northern forces positioned in Mobile after the Civil War. Parading down Government Street surrounded by the Tea Drinkers Society, also known as the “Lost Cause Minstrels,” Cain represented the continued resistance of the South, notably dressed as Chief “Slac,” a Chickasaw Chief whose tribe had never lost to the United States.

It would not be until the 1960s when Julian Rayford wrote Chasin’ the Devil Round a Stump, in which he projects Cain as the spirit of Mobilian Mardi Gras, later petitioning for Cain’s remains to be moved to Mobile and establishing Cain as the monumental figure who saved Mardi Gras. Issues with this depiction include both that of Cain’s legacy as a Confederate soldier who was followed by the Lost Cause Minstrels and Rayford’s own personal history within the South, contributing to the Stone Mountain depiction of Confederate generals. Reviewing the revival of Mardi Gras and the 1960s revival of Joe Cain, connections to the Lost Cause movement during the Civil Rights Movement stand out along the national timeline. However, in the current day, Joe Cain Day is synonymous with the People’s Parade and bringing the community together. Cain’s legacy produces a difficult dichotomy of Confederate support and local celebrations that are depicted within his statue dressed as a mythical figure who opposed the United States. Evaluating the history of how Cain and Raymond left an impression on the city is a challenging task when enjoying the festivities Mardi Gras brings Mobile’s communities.

By Brucie Porter

The legacy of Alabama’s “father of gynecology” masks the exploitation of Black bodies in medicine. On April 19, 1939, the Medical Association of Alabama unveiled a statue honoring Dr. James Marion Sims on the Capitol grounds. Dr. James Marion Sims, known as the “father of gynecology,” began practicing medicine in Alabama in 1836, developing a specialty for “women’s medicine” which focused on complications during pregnancy and childbirth. To gain experience, Sims practiced on enslaved women without anesthesia or consent. Praised for his surgical achievements, Sims is credited with numerous scientific advancements like the invention of the speculum, that continue to benefit patients. However, these advancements could not have occurred without the exploitation of poor, nonconsenting, enslaved women of color. Sims used the bodies of Black women to practice his new techniques. Sims learned from his experiments on Black women to improve his procedures, ensuring that consenting patients never experienced the pain felt by the enslaved women Sims practiced on.

In 2021, Montgomery-based artist Michelle Browder unveiled the “Mothers of Gynecology” monument near the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. The monument, featuring three of the twelve Black women known to have been operated on by Sims, aims to counter the historical narrative of the “father of gynecology.” Browder’s work is not alone in criticizing Sims and his legacy. States across the country, including New York, have opted to remove or redress their memorials of Sims. Despite increasing opposition, Sims’ memorial continues to stand on the Alabama Capitol grounds. For Sims’ supporters, his statue connects Alabama to a history of medical achievement. Yet, by neglecting to acknowledge the enslaved women critical to Sims’ career, his memorial perpetuates the power imbalances central to his medical contributions. Sim’s legacy points to a long history of racial disparities in healthcare that continue to impact people of color. By ignoring this history, his monument stands as a singular, uncritical celebration of white power.

By Lori Sadler

The myth of Emma Sansom’s role in the Civil War has led to a prideful indoctrination into the Lost Cause for students and residents of Gadsden, Alabama. Legend says, Sansom was only 16 years old when Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, in pursuit of Union General Streight, knocked on the door of her family farmhouse in Gadsden. He was looking for someone who could tell him how to get across Black Creek. Sansom not only told Bedford how to cross the creek but guided him to a nearby fjord. This small act earned her a monument and an important place in Confederate mythology. Emma Samson’s life became a symbol of Lost Cause nationalism that would be taught to generations of young people.

Not only was a monument erected to Sansom, but a local school was named after her, sitting along Sansom Avenue. School boards choose names for schools that reflect and shape civic values. By naming a school after a person, they are endorsing that person’s values. This seems to be a pointed way of creating loyalty among middle and high school-aged students, who will grow into adults with a sense of duty to their schools’ namesake.

To drive home this loyalty, on the opposite side of town, the monument sits in front of the University of the Alabama Gadsden, still pointing the students to where Black Creek once ran. Imagine being a student in Gadsden and either attending a school named after a Confederate legend or arriving on campus every day, seeing Emma Sansom on her pedestal pointing behind you. When you are surrounded by this myth during your formative years, it engrains a sense of pride in your “roots.” But is this the pride you want to represent?

By Zion McThomas

The monument “Lifting the Veil of Ignorance” was sculpted in the early 20th century to commemorate the legacy and work of Booker T. Washington. Located in the center of Tuskegee University’s campus, the monument stands as a marker of shallow racial unity in the midst of the Jim Crow Era. Unveiled seven years after Washington’s death, the project and unveiling of the monument were completed with the collaboration of Black Alabamians, white philanthropists, business owners, and educators. Many people from across the country came to set their eyes on the monument in April of 1922. However, the South’s struggle with segregation, racism and racial violence countered the proposed imagery of the monument that highlighted Washington’s form of racial uplift and at the same time slighted DuBois’ ideas around racial uplift.

The monument is a physical presentation of the complexities of racial politics. This African American monument represents the tenacity of Washington and the Black community as it was partially funded by Black people. It also represents the efforts of white supporters to align themselves with a model of racial uplift that did not demand radical changes to the political system. Even in the design of the monument, which features a young Black man in slave-like clothing having the cloth lifted from his eyes, Washington is presented in a manner that fits his passive ideal of a Black South that thrives in technical and agricultural education. “Lifting the Veil of Ignorance” rides the tightrope of praise and negligence as it pays homage to the Founder of Tuskegee while contorting around the aggressive violence of the Jim Crow Era.

By Kevin Fabery

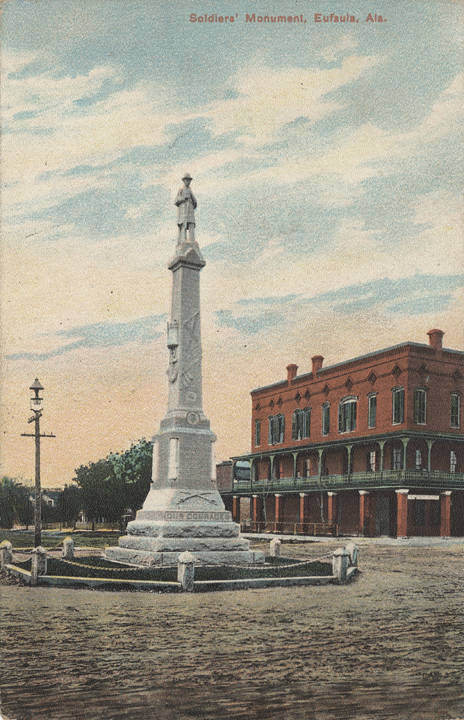

The Confederate Monument in Eufaula, Alabama, was unveiled in 1904 through the efforts of Barbour County’s United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC) chapter. The UDC, as their organization’s name suggests, were women who were either children during the Civil War or were born after the war to former soldiers of the Confederacy. Since 1866 memory groups such as the UDC worked on rewriting the history of the Civil War through schools and public monuments as a war fought for states’ rights instead of slavery and white supremacy. At the unveiling of the monument, Mary Clayton, the UDC chapter President, declared they sought “to unite with the Confederate Veterans in obtaining an impartial history of the struggle, that the children of our Southland may be taught to reverence the brave men of their own families who laid down their lives in defense of the purest principle of patriotism in 1861-1865.” As she stated, the theme of the Eufaula Confederate monument, as intended by the UDC was to portray the Civil War as the issue of states’ rights instead of white supremacy and slavery. The UDC funded the monument’s construction in order to allow people to see it in a public space and shift the location of memorialization from the cemetery to the city. Their leaders stated at the unveiling that the Civil War was a fight for states’ rights in which Confederate soldiers were brave men who fought with honor rather than maintain slavery and white supremacy.

The monument’s construction coincided with the thirtieth anniversary of an act of white supremacist violence carried out on November 3, 1874, by former Confederates and white residents against black voters in which at least ten men died and over eighty others were wounded; Reconstruction in Alabama ended shortly after this event. A historical marker erected in 1979 on the site of the riot concluded with the sentence, “This bloody episode marked the end of Republican domination in Barbour County,” while ignoring the assault of black voters by white ex-Confederates and residents. Eufaula’s public memory largely ignored this history in favor of foregrounding the city’s Lost Cause Narrative of the Civil War.

By Matthew Poirier

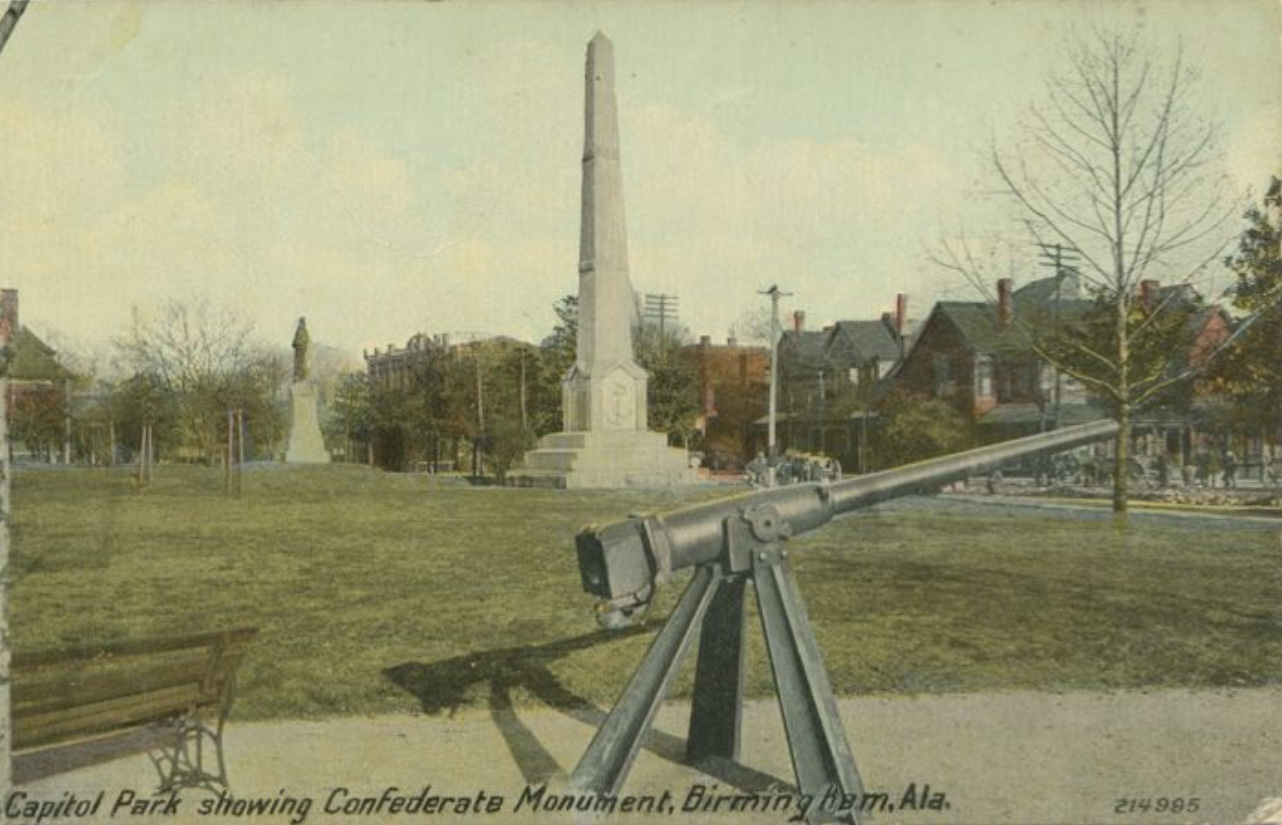

Birmingham, Alabama was founded in 1871, and almost by magic, became an industrial boomtown by the 1890s. City leaders created a center of commercial prosperity as well as a usable past that linked the city to the Confederacy and their values of white supremacy and conformity. These values gave the city’s white laborers a taste of the wages of whiteness, where they reveled in a shared, constructed white past, and further separated themselves from the Black working class.

City leaders decided in 1894 to build a monument in Linn Park to “give the youth of the South the enviable example…” of how Confederate values of white supremacy were “still to be victor.” Even though their city didn’t exist during the war, city leaders knew that celebrating the Confederacy was essential to their control of southern society. Racial equality threatened to disrupt Birmingham’s social and labor order. A narrative celebrating white unity under the Confederacy helped ensure white unity in the city. As the leader of the Alabama United Confederate Veterans boasted at the unveiling ceremony in 1905, the recent “supreme achievement of Anglo-Saxon civilization” in Birmingham “was the cheerful spirit of that footsore man in gray.” White Birmingham citizens did justice to Confederate soldiers as they continued in the fight against “the hideous specter of a threatened race equality” in the city. The monument was conceived of around the same time when Alabama’s constitution legally stripped African Americans of the right to vote and set up state mandated Jim Crow segregation, all fights against the “threatened race equality.”

The monument gave white laborers a sense of belonging outside of their economic interests. Orators at the unveiling ceremony criticized those who were in a “blind rush for material power and prosperity” and asserted that they did not emulate Confederate soldiers’ “devotion to duty and patient sacrifice.” This was a warning to those who thought about striking for better conditions as striking was against their Confederate legacy and thus a crime against their race.