Artist Rodell Warner reinterprets Audubon’s writings, etchings and lithographs

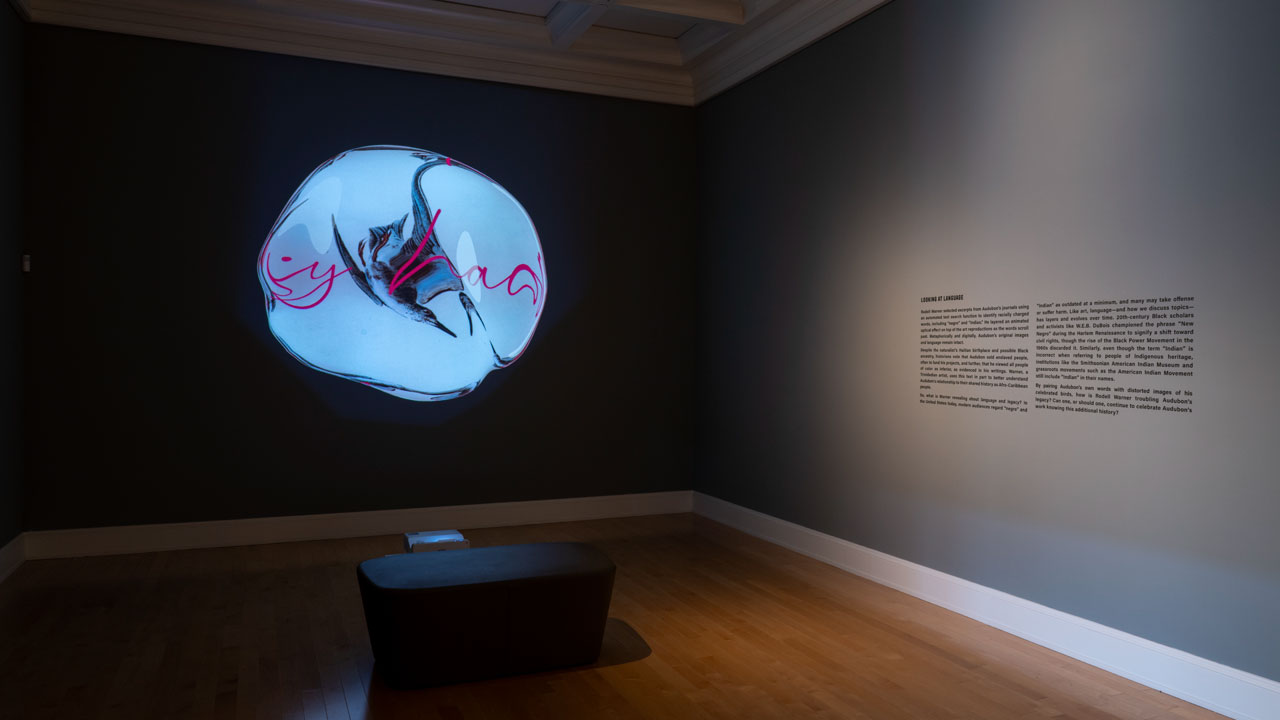

Faint sounds of bird calls welcome visitors as they enter the Louise Hauss and David Brent Miller Audubon Galleries at Auburn University’s art museum. Projected in full on the gallery wall is a circular, waterlike animation of a black tern as initially depicted by 19th-century naturalist John James Audubon. The bird appears to dive and quickly change course as the video morphs. Bright pink cursive writing scrolls in from the right, the applied effect swirling the script across the image.

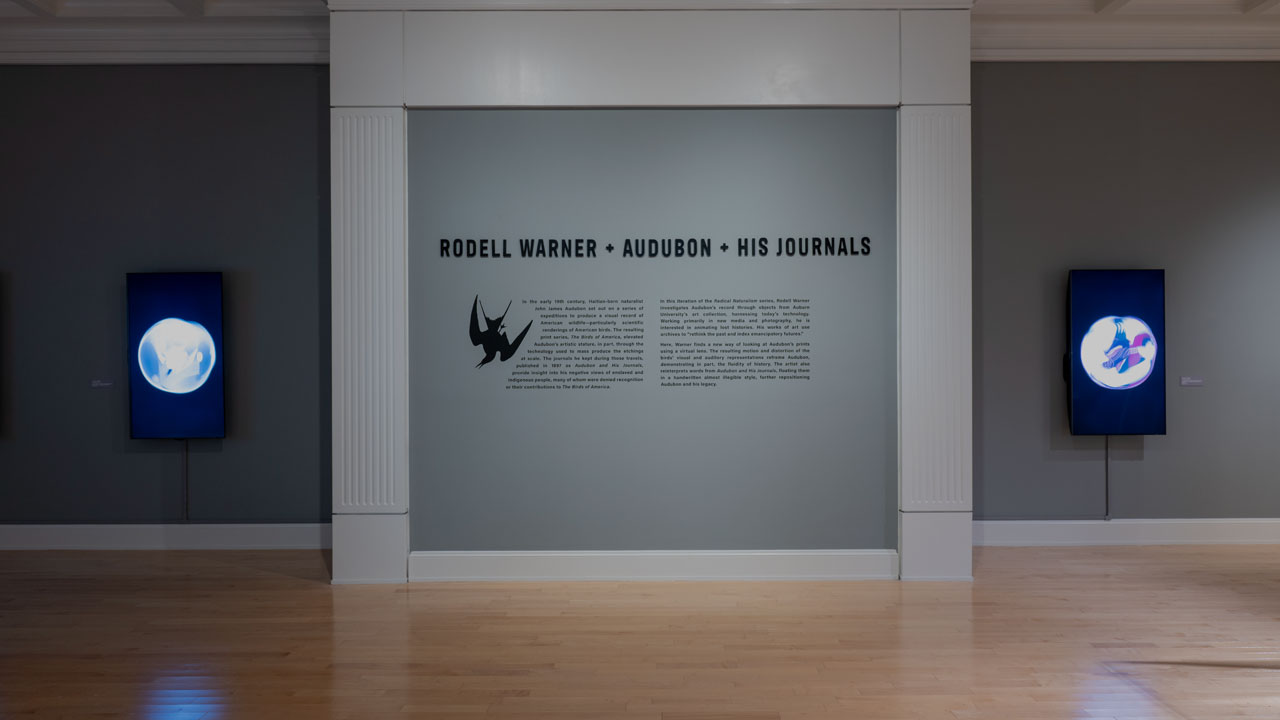

The object is on view at The Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art as a part of “Rodell Warner + Audubon + His Journals.” Open through Sunday, July 6, the exhibition includes six prints by John James Audubon paired with seven digital videos and an online generative website by artist Rodell Warner. His works have been exhibited internationally, including at the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Pérez Art Museum in Miami, Florida. The exhibition is the seventh installment in the museum’s ongoing “Radical Naturalism” series. Through “Radical Naturalism,” the museum invites contemporary artists inspired by the natural world to research university collections and engage with, question and critique John James Audubon’s legacy.

“Warner affects the object reproduction by overlaying an animated digital lens and handwritten words from Audubon’s journal,” said Chris Molinski, the Janet L. Nolan Director of Curatorial and Educational Affairs. “The birds and their calls remain intact, but the distortion allows us to see the image differently and try to read Audubon’s original text. Warner’s approach underscores history and the way we interpret it as an evolving process.”

Auburn’s Louise Hauss and David Brent Miller Audubon Collection includes 120 etchings and lithographs from the Double Elephant Folio publication “Birds of America” and the three-volume set of the “Viviparous Quadrupeds of North America.”

“These objects are a cornerstone of the university’s art collection,” said Cindi Malinick, museum executive director. “Curating exhibitions like Warner’s emphasizes the work of creative scholarship — and the role of university museums — in making concepts more accessible, generating engaging ideas and broadly benefiting society.”

Born in Haiti, John James Audubon spent his life hunting and trapping North American specimens, documenting the species of birds, insects and plants he encountered. Though celebrated, historians and biographers in later years uncovered his findings contained scientific inaccuracies. He also enslaved people and supported the institution of slavery in his publications. Others contributed significantly to his work artistically and scientifically — from fellow artists to people of Indigenous cultures — and went unacknowledged by the naturalist.

Artist Rodell Warner explained that he used language in this exhibition to share details of the context within which Audubon’s works were made.

“In his journals, he documents hunting excursions on which he collected the birds he illustrated, encounters with Indigenous communities, and the ways that they, along with enslaved African Americans that he owned, were instrumental in performing the labor that supported his art practice.” Warner said. “In viewing his work without details of these contexts, one would be unaware of the labor of any others at all, attributing the gargantuan effort that must have been exerted to create The Birds of America to Audubon alone.”

“I’ve made works that unite text and image to share what I’ve learned about the world Audubon operated in, and how African Americans’ and Native Americans’ labor and agency informed it,” he added.

Warner also shares Audubon’s Caribbean heritage, serving as a point of departure for his work. He is recognized for his innovative use of new media and photography to animate and reinterpret historical narratives. His work often bridges the digital and physical realms, using projections and gifs to bring archival materials to life.

“Early in my research, I learned that Audubon was born on San-Domingue, now called Haiti, where his father owned a sugar plantation and enslaved people of African descent,” Warner said. The artist also learned that Audubon’s father took him as a child to France, as tensions mounted from the Haitian Revolution. Audubon’s biological mother was of mixed African and European ancestry.

“This all made me curious about Audubon’s relationship to the Caribbean and to people of African descent, which led me to read — and to use search tools to measure and codify the contents of —PDFs of his published journals.”

Warner viewed Auburn’s art collection via the museum’s online database. “My process for selecting archival material for this exhibition was almost entirely about assessing the forms of the illustrations to find images of birds that interacted in interesting ways with my animated virtual lenses,” he said. “There are ways that the rotating irregularly shaped lenses can animate figures, like Audubon’s birds, to give them the appearance of moving, of being alive. This only happens with some figures, depending mostly on their posture, so I looked for works that took well to this kind of animation.”

Warner’s campus engagement includes a visit in March, during which he will visit classes to discuss his work with students and faculty. He will present an in-person talk at The Jule on Thursday, March 27 at 6 p.m. as a part of the museum’s weekly “Common Grounds” series.

The museum offers free admission to students, faculty, and the public. Faculty may also use the art collection to enhance their research and teach with objects in the galleries or Study Room. For more information about this and other museum programs, visit jcsm.auburn.edu or contact jcsm@auburn.edu.