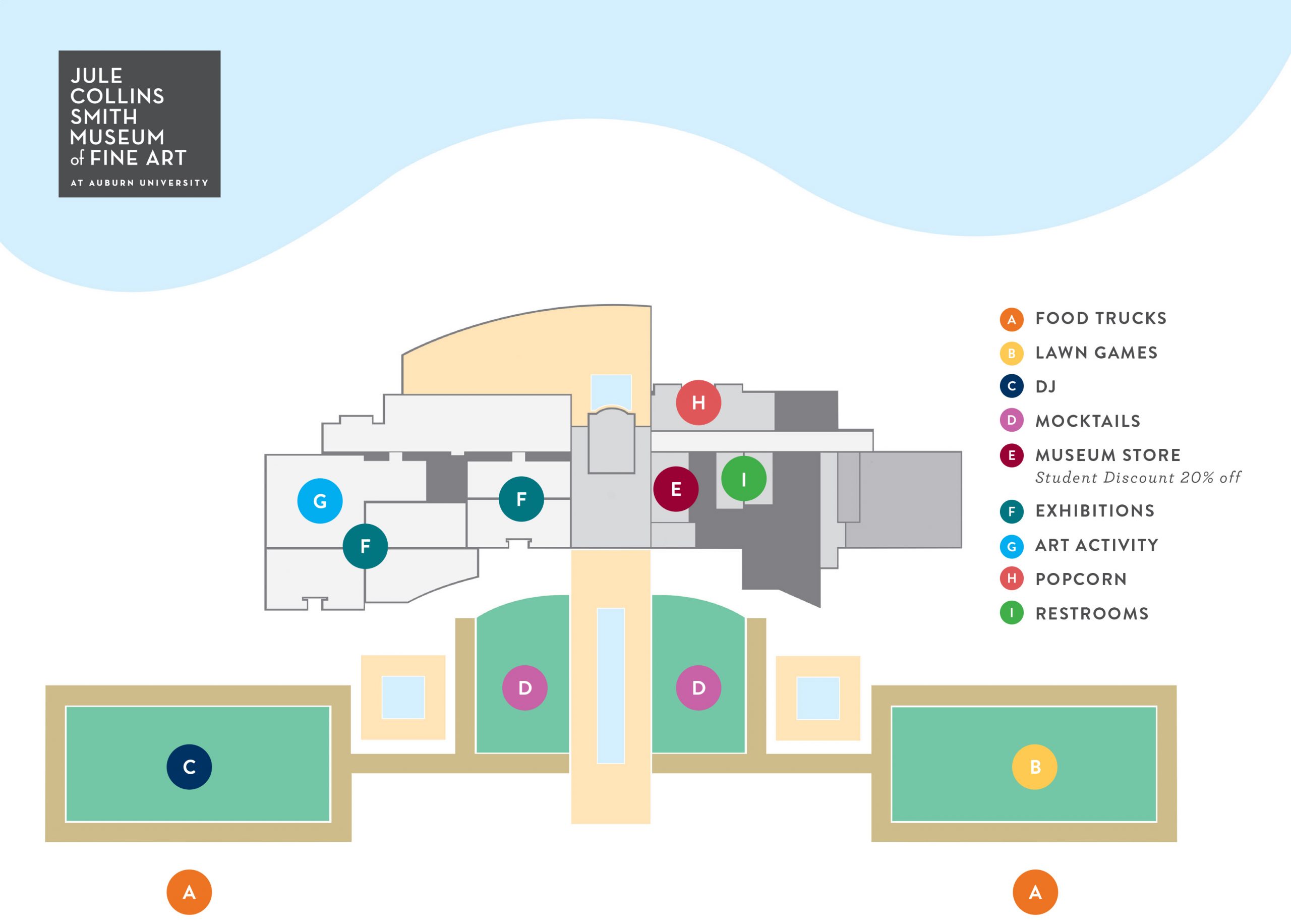

Southern Humanities Review awards an annual $1,000 prize and publication opportunity for a poem of witness in honor of the late poet Jake Adam York. Presented in October by the Jule Collins Smith Museum of Fine Art at Auburn University, the Auburn Witness Poetry Prize event features the recipient and judge in conversation at the museum.

This program is likely expected to reach full capacity, so help us anticipate numbers by pre-registering. Auditorium seating is open on a first-come, first-served basis. Please use all available seats to ensure we provide an engaging experience for everyone.

In 2019, Joy Harjo was appointed the 23rd United States Poet Laureate, the first Native American to hold the position. Born in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Harjo is an internationally renowned performer and writer of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. She is the author of nine books of poetry, several plays and children’s books, and two memoirs.

Samyak Shertok’s poems appear or are forthcoming in Best New Poets, Cincinnati Review, Gettysburg Review, Gulf Coast, Iowa Review, Kenyon Review, New England Review, POETRY, and elsewhere. Originally from Nepal, he holds a PhD in Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Utah and is currently a Hughes Fellow in Creative Writing at Southern Methodist University.